Citicorp Center: A close call with disaster

- download the full article here.

High above Manhattan, a team of structural welders were secretly working through the night strengthening connections in a race against time. Hurricane season was fast approaching and even a modest storm could put the lives of up to 200,000 people at risk. The fifty-nine-storey skyscraper they were strengthening was supposed to be a marvel of structural engineering but instead was poised to be one of the greatest engineering disasters of all time.

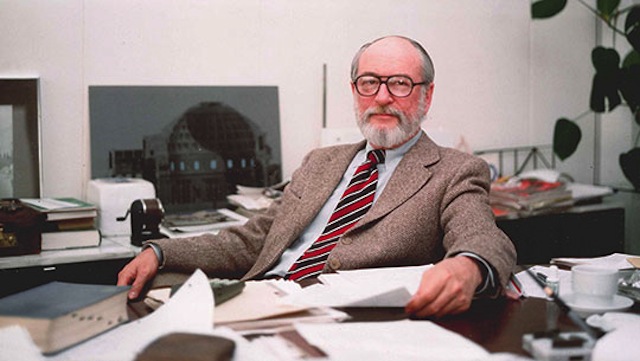

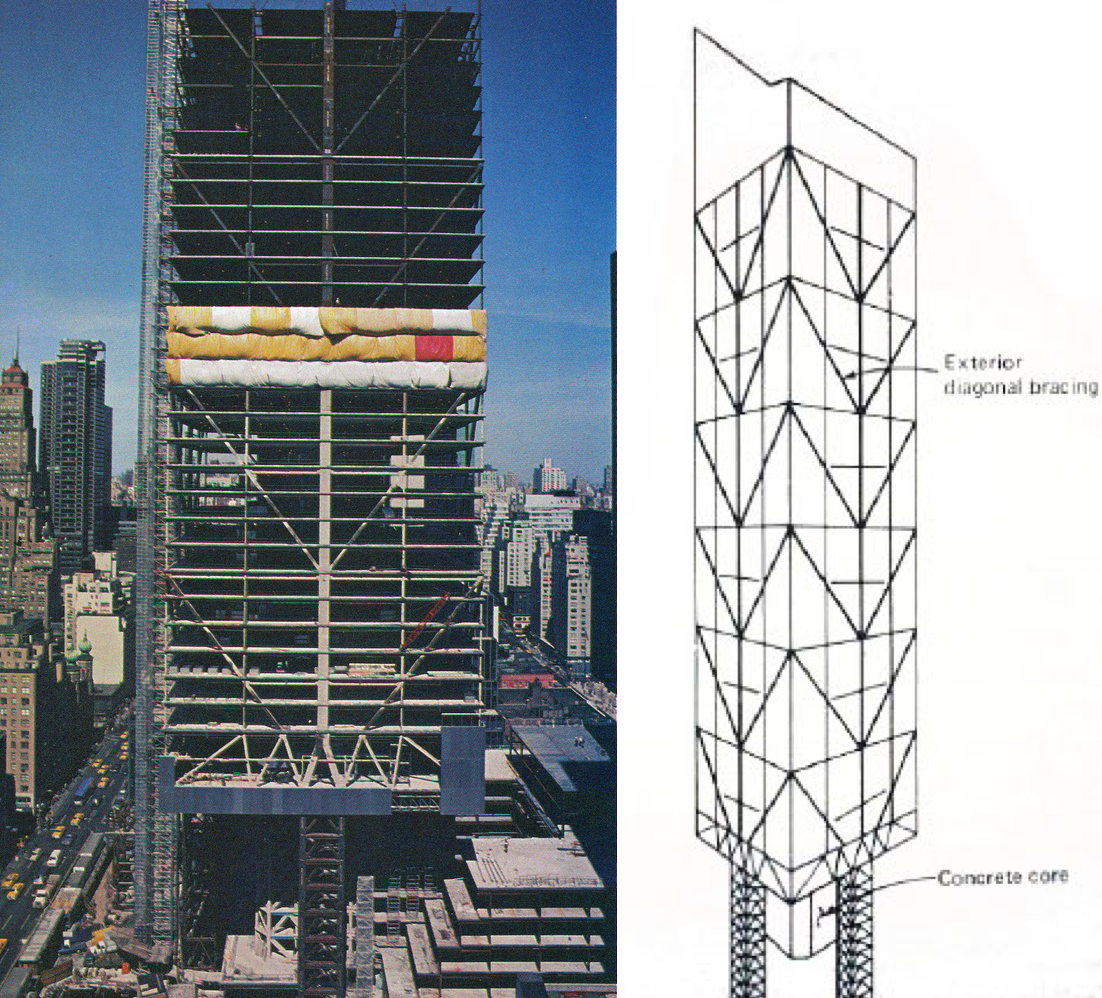

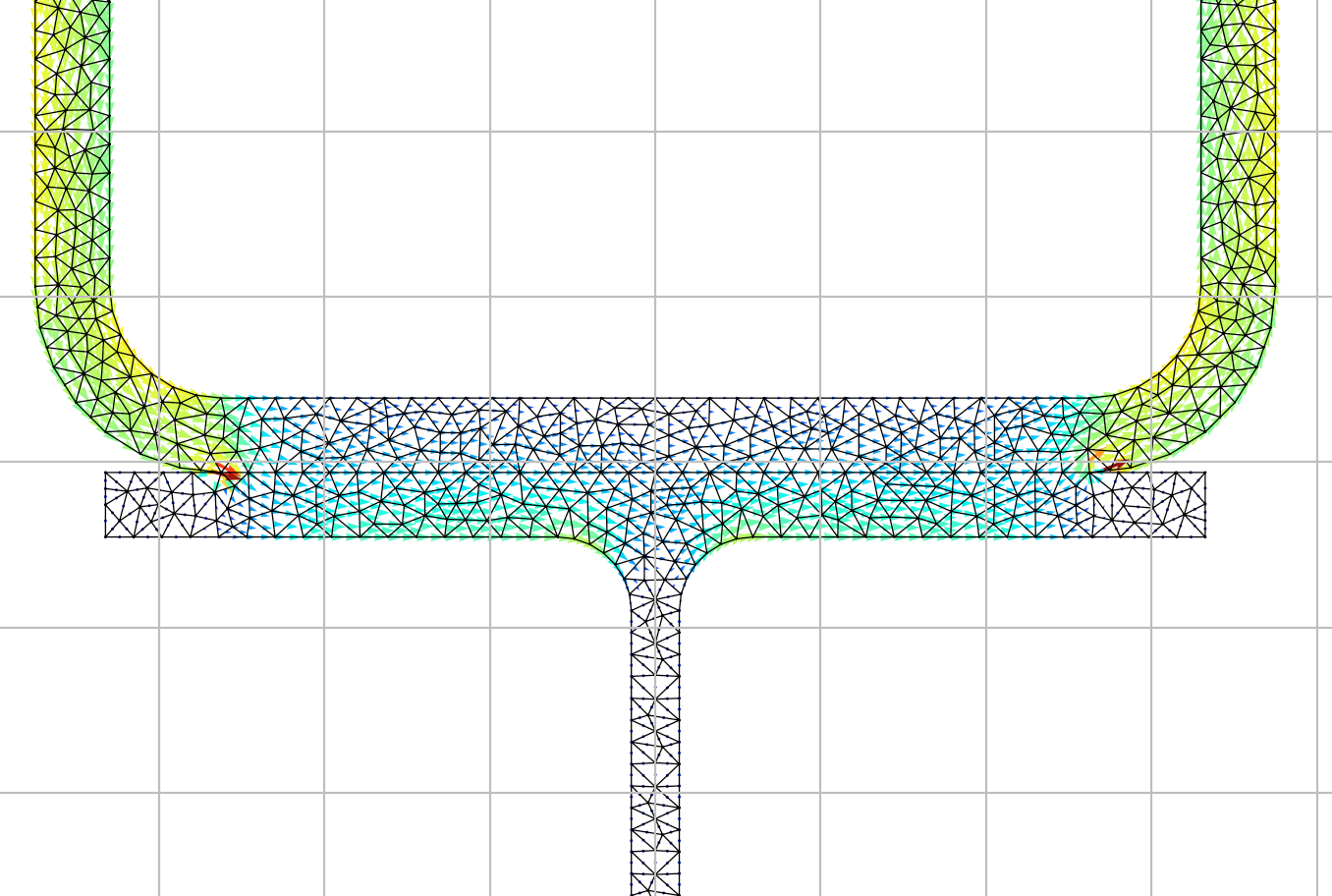

It all started in June 1978, with a phone call from an engineering student to William LeMessurier. LeMessurier was the structural engineer behind the uniquely designed Citicorp Centre Tower, which at its completion in 1977 carried the title of seventh tallest building in the world. To avoid St. Peter’s Church at the corner of the site, LeMessurier placed four nine-storey high structural columns at the centre of each face rather than at each corner. This scheme, in conjunction with an inverted steel chevron bracing system, cantilevered the corners of the 280 metre tall steel structure, 22 m out over the church. The engineering student had phoned to ask about the location of these columns and their impact on the lateral stability of the structure. LeMessurier reassured the student and pointed out that, in his opinion, the columns were ideally placed to resist quartering winds (wind striking the building diagonally at its corners).

LeMessurier, also an adjunct professor at Harvard and MIT, decided that this concern would form the basis for an interesting lecture for his engineering students. In the original structural design of the steel braces, only perpendicular winds were considered, as this was all that was required by New York City’s building code at the time. However, in preparation for his lecture LeMessurier also set out to verify the strength of these braces when subjected to quartering winds. What he discovered was both surprising and chilling, and set in motion a series of events that were kept secret for almost twenty years.

A fatal flaw

The function of the steel bracing system was not only to provide lateral stability, it also supported half of the vertical load of the structure. This meant that the connections in the bracing system were very sensitive to changes in tensile loading. When LeMessurier ran his calculations on the quartering winds he found that, in half of the chevrons, the force from wind loading had increased by 40%. LeMessurier was relieved to find that the structural sections could resist this increase in force. However, when he looked at the bolted splice joints, he found that a 40% increase in wind force more than doubled the forces in the bolts. His following realisation would send shivers down the spine of any structural engineer: it would only take a one in sixteen-year storm to topple over his structural masterpiece, a far-cry from the one in five-hundred-year event it was supposed to be designed for. As LeMessurier reported years after the event, “that was very low, awesomely low.”

LeMessurier began looking for anything he could use to justify the building’s integrity. He tried to factor in the building’s tuned mass damper, one of the first ever installed in a skyscraper. However, this only reduced the failure probability to a one in fifty-five-year storm and it couldn’t be relied upon in such an event because it required power to be operational. He travelled to Canada to request more thorough testing of the building in the Boundary Layer Wind Tunnel at the University of Western Ontario. But after considering the dynamic response of the building, they reported slightly increased wind pressures! By this time, it was late July and hurricane season was approaching. LeMessurier realised that, in the face of litigation, bankruptcy and professional disgrace, the only way to avert catastrophic disaster was to blow the whistle – on himself.

A battle plan

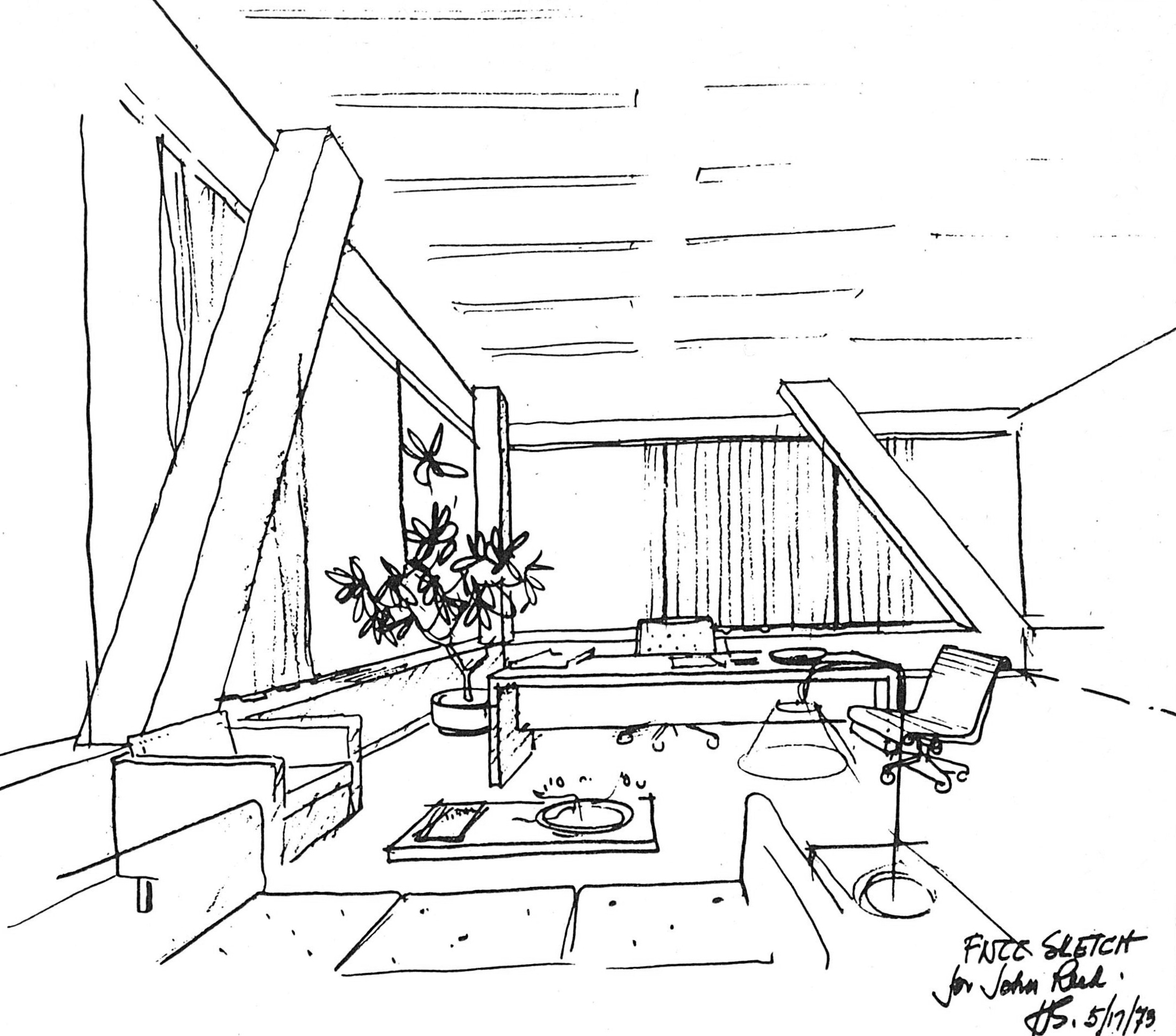

During a series of confidential meetings with the architect Hugh Stubbins, the Citicorp board and Citicorp’s engineer (Leslie E. Robertson), LeMessurier outlined his plan to fix the braces by welding 50 mm thick steel plates across the splice connections on over two hundred of the bolted joints. A band-aid solution in the truest sense! During the conceptual design of the building, LeMessurier had tried to convince Stubbins to express the structural beauty of the braces on the exterior of the building. In what proved to be extremely fortunate, Stubbins had resisted this offer. Now instead the steel bracing was clad in fireproofing material, making diagonal features of the structure visible in several offices. But more importantly, it meant that the structural bracing was easily accessible for strengthening.

At an ethical crossroads, the team decided it would be best not to alert the public to the fatal flaw in the structure due to the disproportionate amount of panic that would ensue and instead issued a vague press-release detailing minor maintenance and strengthening works over the coming month. By lucky coincidence, all the journalists from the major newspapers were on strike during this period, so no-one followed up on the story in detail. Despite their publicly calm approach, the team did develop a response plan in the event of a wind alert in conjunction with the mayor’s Office of Emergency Management. Under this plan, the building and surrounding neighbourhood would be evacuated and the Red Cross would mobilise two thousand workers to provide food and temporary shelter. The Red Cross estimated that the number of people that may have to be evacuated would be almost 200,000.

A race against time

The strengthening work began almost immediately and was carried out in military-like fashion and secrecy: at 5pm teams of carpenters would put up protective screens around the bolted joint and remove the fireproofing material, from 8pm welding would commence and continue until 4am, when labourers would clean everything up before the first office workers arrived the next morning. LeMessurier approached the strengthening with the precision of a true structural engineer.

“I was constantly calculating which joint to fix next, which level of the building was more critical, and I developed charts and graphs of all the consequences: if you fix this, then the rarity of the storm that will cause any trouble lengthens to that.” - William LeMessurier.

Only a few weeks after the commencement of works, the weather services reported the news that everybody had been dreading, Hurricane Ella was heading for New York. LeMessurier stated that the most critical joints had already been fixed and that backup power had been provided to the tuned mass damper, meaning that the building could now resist a one in two-hundred-year storm. LeMessurier recalled that “everybody was sweating blood” as the hurricane approached. However, before they had to make the decision to put the evacuations in motion, the storm veered from its heading and began moving back out to sea.

Crisis averted

Just over a month later, the welding was completed and the building was now strong enough to withstand a one in seven-hundred-year storm. A minor legal tussle ensued in which LeMessurier offered Citicorp US$2 million, which was the value of his insurance policy. But this was reportedly far less than the estimated costs of repair.

Since the story became public in 1995, opinions relating to LeMessurier’s ethical conduct have been generally positive. Arthur Nusbaum, the steel contractor for the strengthening, argued that:

“It started with a guy who stood up and said, ‘I got a problem, I made the problem, let’s fix the problem.’ If you’re gonna kill a guy like LeMessurier, why should anybody ever talk?”

There is a lot to learn from engineering disasters of the past; problems with technical theories can be highlighted and poor engineering practice exposed. Even though the basis of this near engineering disaster was technical in nature, the most important conclusion from the events at the Citicorp Centre is the triumph of ethical engineering.

References:

- Morgenstern, J. (1995, May 29). The Fifty-Nine-Story Crisis. The New Yorker, pp. 45–53.

- Brady, S. (2014, February). Citicorp Center Tower: failure averted. The Structural Engineer, pp. 14–15.

- Kremer, E. (2002, April 06). (Re)examining the Citicorp case: Ethical paragon or chimera. Retrieved February 17, 2017, from Cross Currents, http://www.crosscurrents.org/kremer2002.htm.

Leave a comment