Design and construction of the Sydney Opera House roof sails

- download the full article here.

Almost every time I tell someone from The Netherlands that I grew up in Sydney, they can’t help telling me how much they’d love to visit the Sydney Opera House! I know I’m surrounded by engineering and architecture enthusiasts here in Delft and I can’t argue with them! With its white sailed roof, set on the backdrop of Sydney Harbour, the Sydney Opera House is arguably one of the most iconic structures of the 20th century.

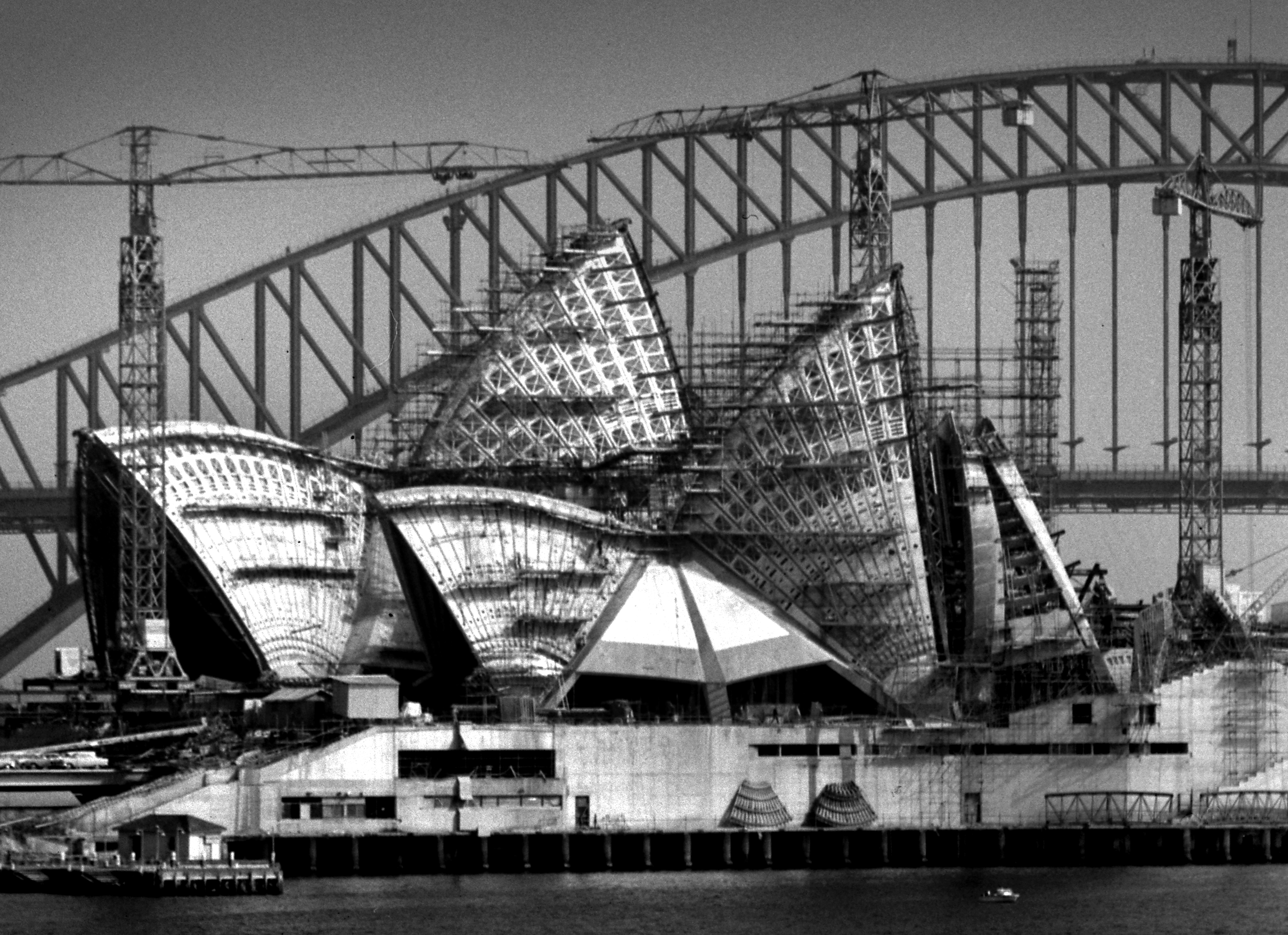

It took 16 years of design and construction to realise this architectural monument and, with its final cost over 10 times the initial budget, the project was never far from the eye of the public. Architectural critics condemned its form as lacking function while engineers, taking cues from the designs of Nervi and Candela, argued that the roof was structurally illogical. All the while, the state government had to continually convince the public (and themselves) that this was all was worth the price tag of €620 million (in today’s money).

Over forty years have passed since the Sydney Opera House was officially opened. Each year it is host to more than 2000 performances that are attended by more than 1.5 million people. As well as being a successful artistic hub, the architectural status of the Opera House has been confirmed by its inscription on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Design Development

In submitting the winning design, the architect, Jørn Utzon, conceived the scheme of the roof without any engineering consultation or advice. When head engineer Ove Arup and his team began their preliminary design of the roof, they quickly realised that the thin shell Utzon had envisaged would not be possible. This was because the shape of the roof introduced large bending moments, regardless of any conceivable structural system.

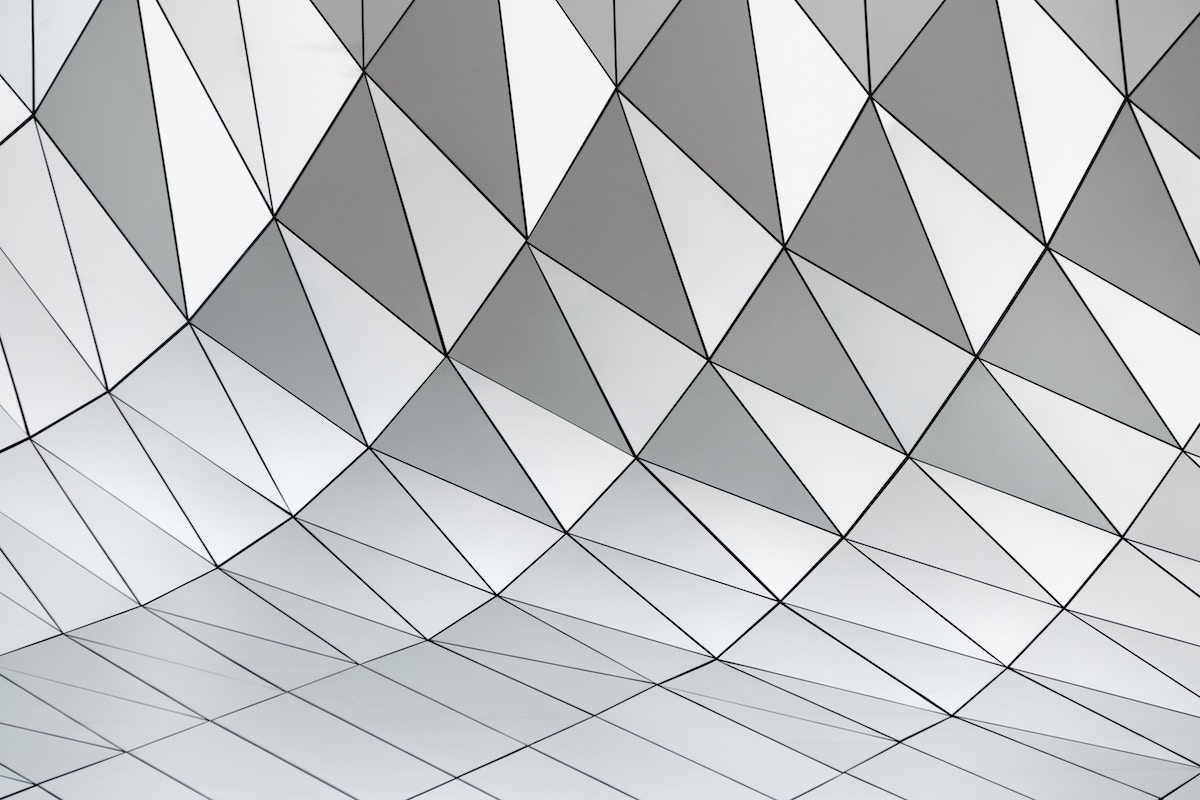

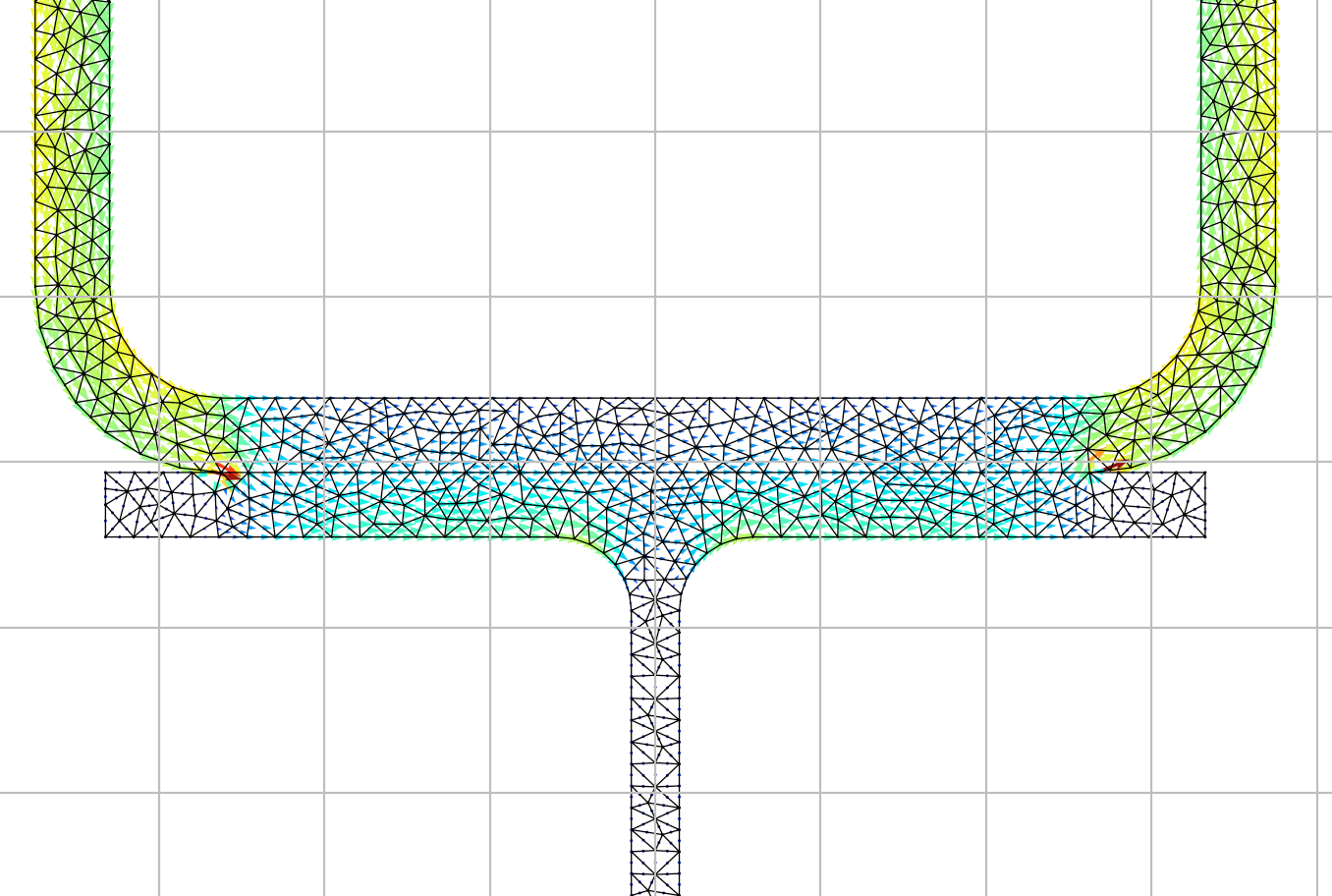

While the base of the building was constructed, Arup and his team spent six years working with Utzon, refining the design of the roof to arrive at a solution that was architecturally pleasing, structurally sufficient and relatively cost effective. Arup canvassed at least 12 iterations for the geometry of the shells, ranging from parabolas to arcs to ellipsoids. The final solution involved forming each shell with segmented post-tensioned, precast concrete ribs, all having their external surfaces described by the same sphere. By fabricating similar elements forming part of a spherical geometry, it was possible to maximise the use of repetitive elements in the construction of the shells.

Structural Analysis

Until the design of the Sydney Opera House, structural engineers working in the building industry had not used computers for structural analysis. All calculations were carried out manually, with the assistance of slide rules, logarithmic tables, and very rarely with calculating devices. However, even Ove Arup was humbled by the task, which required the iterative and ever evolving design of a complex, three-dimensional structure: ‘It is difficult to visualise how the necessary calculations could have been made without [computers]’.

The program that was adapted for the analysis was originally designed for structures with 18 or fewer joints. The most complex framework analysed in the design of the Opera House had 136 joints and took the computer nearly four hours to analyse the five load cases. In addition, preparation of the input data took almost three weeks. Although this seems tediously slow by modern standards, it has been estimated that the computer calculations saved almost 10 years of human work.

Construction

The roof structure consists of over 2,400 precast arch units placed on cast-in-situ concrete pedestals. The adjoining arch segments were constructed on a steel centering and stressed together to form a stable structure. Utzon apparently had an affection for the structural detailing of the ribs and chose to make the smooth surfaces of the concrete structure a feature of the design. Once the rib segments were in place, the shells were laterally stressed to enable the desired structural behaviour. Approximately one million tiles were placed on the roof surfaces in the form of repetitive precast panels.

Completion

The Sydney Opera House was officially completed in 1973 with over 400,000 structural engineering manual hours and 2,000 computational hours. The structural design methods used by Ove Arup and his team paved the way for modern engineering practices, which are heavily reliant computational analysis and, like with the Opera House, enable the design of highly complex structures. While the final cost of the project was relatively high, the Sydney Opera House stands as a monument to structural engineering and continues to inspire the hearts and minds of people all over the world.

References

- Arup, O. N., & Zunz, G. H. (1969). Sydney Opera House. The Structural Engineering, 47(3), 99-132.

- Trafas White, Z. Computers and the Sydney Opera House. Retrieved May 22, 2017, from https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/computers-and-the-sydney-opera-house

- Sydney Opera House: Our Story. Retrieved May 22, 2017, from https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com

Leave a comment